[tl;dr — about a quarter of the time]

Every year as state legislative sessions get started, there’s a flurry of scary headlines of the form: “[State] [Party] files bill to do [thing I find scary, bigoted, or irresponsible]”. It’s tough to know from reading whether this is something you should get concerned about.

Maybe you should, maybe this is the next big bill that will make your state a national embarrassment, spark economic boycotts, and cause your Governor to lose his re-election campaign. Or maybe this is a crackpot bill and it’s not going anywhere, so don’t waste your time.

Good reporting can help to fill this in – is this a senior legislator, are they a known kook, etc. But there’s another, more general piece of this context that I wanted to help fill in. My question is, overall: how often does a bill go from being filed (its first official step) to becoming law (its final official step)?

First you need at least a rough understanding of how a legislature works. You could watch the classic Schoolhouse Rock video:

Or I’ll give you the 60-second version (skip to the next paragraph if you already know how it works): a legislator files a bill, which is a thing that they want to become law. The person who files is called the “sponsor” or “patron.” It’s referred to a relevant committee, which is made up of a subset of the legislators in their chamber (the House or Senate, usually). If a majority of the members of the committee vote for it, then it goes to the full chamber, if it gets a majority vote there then it’s handed over to the other chamber, and the committee and full-chamber process repeats. After that, the governor signs the bill then it becomes a law. (Exact details vary by state, but it’s probably pretty close to that, unless you’re in Nebraska. Find your legislature’s website and they probably have a “how a bill becomes a law” page to explain their version of the process.)

The important thing to know is that bills can (and do) fail at any of those steps in the previous paragraph. Depending on the rules of the chamber, if the leadership doesn’t like the sponsor, or the bill, it may never even come up for a vote. Or those votes will happen in a closed session of a subcommittee, where the public doesn’t get to see which legislators voted to kill a bill.

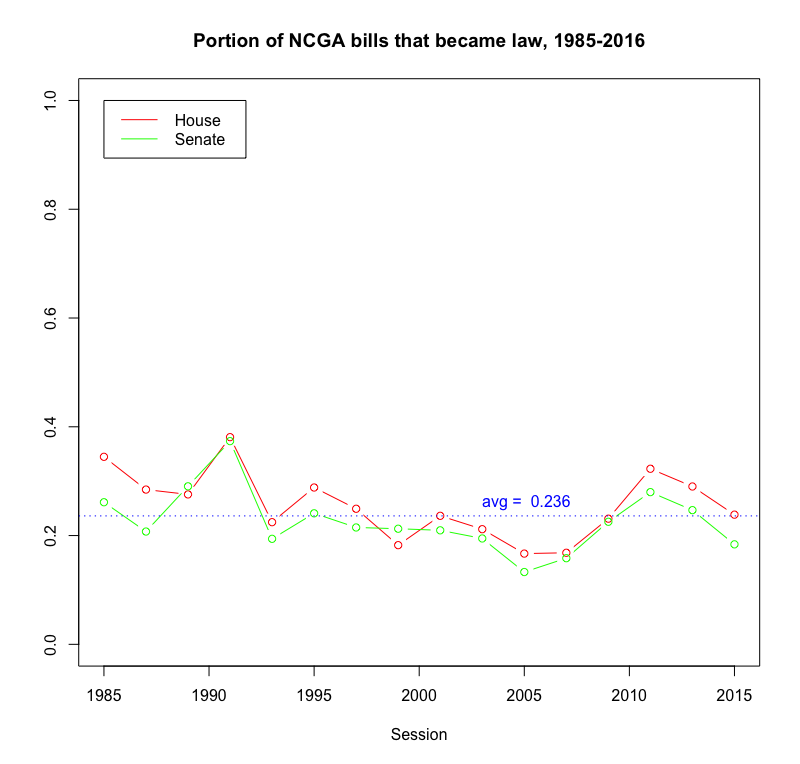

Back to the point, I downloaded the history of every bill filed in the North Carolina General Assembly (NCGA), my state legislature, since 1985 and parsed out its fate. The answer to my question was 23.6% — just under a quarter of our bills actually become law.

So when you see that scary headline, keep in mind that a bill being filed is actually more likely to fail without becoming law, than to succeed. I’m not telling you to ignore it, or not to fight it — on the contrary, this should encourage you to fight. Be part of the reason that the bill you don’t like failed. Get out there and kill that bill.

I’m sorry, I had to. I don’t even like this movie, but the pun was just sitting right there.

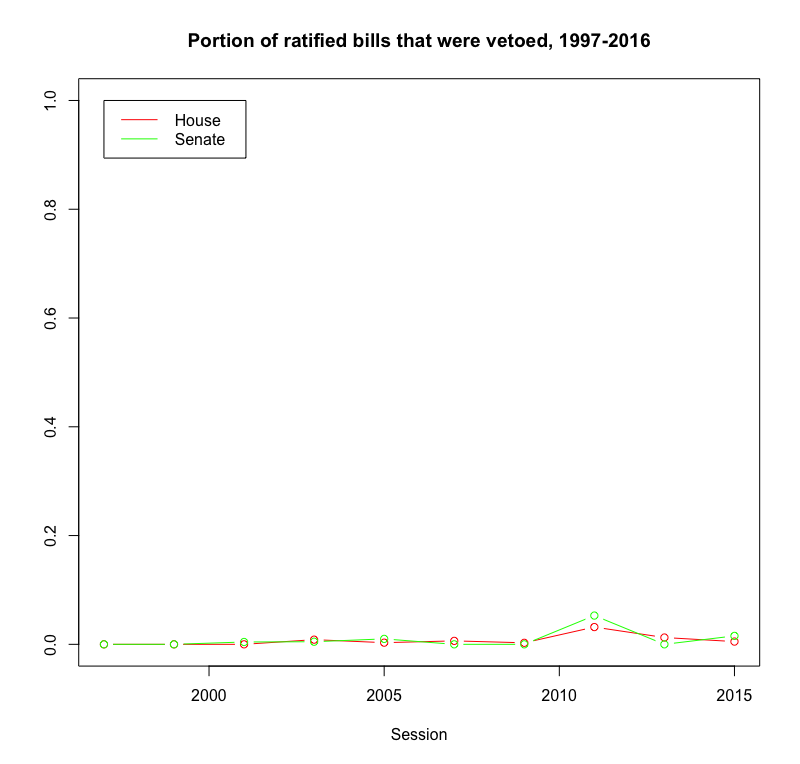

Since I’ve got all this data, I decided to answer another question quickly: how often does the governor veto bills? This next chart shows how often, when given the option to sign or veto a bill, the governor chose to veto:

So, uh, not often. There’s a tiny little spike in the 2011-2012 session, when we had a Democratic governor and a Republican-controlled legislature, but even then it barely registers on the chart.

If you got this far and you think this was at least a little neat, I want to do something for you. I’ve got all this data downloaded and parsed, and I’m sifting through it, but I want to know what questions I should try to answer. Here are a few that I want to tackle next:

- a breakdown of where bills fail – in committee, in the full chamber, in the other chamber.

- which legislators get more of their bills passed?

- are bills with more co-sponsors more likely to pass?

Can you come up with others? If you have a question or a hypothesis, tweet it at me @jebstuart and I’ll see if I can answer it.

Following are a few notes about methodology & assumptions:

Why start in 1985? That’s as far back as the easily-available online records go (and almost my full lifetime) so I’m calling that “the relevant dataset”. I feel like it’s enough data to get a good sense of the overall pattern.

Why are there only data points every other year? The NCGA operates in two-year sessions (e.g. we’re currently in the 2017-2018 session), and that’s how their bills are filed.

What about resolutions? An NC legislator can file a “bill” or a “resolution”, but resolutions are typically honorary things without legal weight, so I excluded them from the dataset as not relevant to the question I wanted to answer.

What about “extra” (or “special”) sessions? I didn’t include them either. They’re typically single-purpose sessions with few bills filed, and I didn’t want to clutter the data.

Are the numbers the same for [other state]? Not the exact same, for sure. Maybe similar, maybe not. I have a hunch these results are probably “typical”, within a standard deviation or so, but I can’t verify that without a lot of work that I’m not going to do.